Egyptian Pound Devaluation: Causes and Consequences.

One month ago, Hassan, a friend of mine, bought 1300 USD (U.S. Dollars) for pocket money on his trip to Hungary. On his return, one week later, Hassan became 260 EGP (Egyptian Pounds) richer than he was upon departure. Had Hassan tried to buy the dollars two days later, he wouldn’t have been able to join his friends in Hungary. Banks limited dollar exchange -so as to avoid a currency crisis- to emergencies. You had to inform the bank 24 hours earlier, and they would decide if you deserve the transaction or not. The Egyptian Pound had been undergoing a series of devaluations for the past month, 6.64 EGP are sold for 1 USD on the second anniversary of the revolution. Rumor has it that an IMF loan negotiation is behind all (of) this (a topic I have discussed earlier).

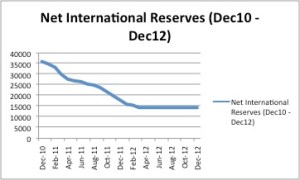

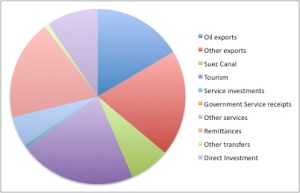

To close followers of the Egyptian economy, devaluation was not surprising. The central bank’s foreign reserves plunged from $36 billion before the revolution to $15 billion by the end of December. The reason for that is that the real economy’s share of exports constitutes only 20% of the demand for EGP while Tourism, Suez Canal Revenues, Remittances, Oil and Foreign Direct Investment make up 22%, 7%, 18%, 17% and 9% respectively, adding up to 73% of the demand for EGP. Given the turmoil caused by the January 25th uprising, lack of security and political uncertainty, much of this demand disappeared as tourists and foreign investors fled and the central bank had to step in, creating artificial demand for the pound (at the expense of USD reserves) in order to sustain a reasonable exchange rate for the pound. The Egyptian Central Bank’s monetary policy has price stability as its “primary and overriding objective” and Egypt has already been employing a managed float system since the day it abandoned its dollar peg in 2003. On the 29th of December, the central bank issued a statement that the rate of decline of foreign reserves is unsustainable and that a policy shift will take place. Since then, the EGP lost 4.7% of its value. This is not the end, it is expected that the USD/EGP rate will reach around 7.5 by the end of 2013.

Basic textbook economics tells us that such devaluation (and currency depreciation in general) is favorable to the Egyptian economy. The rationale behind this is that it will make Egyptian exports more competitive in international markets, boosting exports, production and employment. Furthermore, the increase in import prices will drive consumers to replace them with local alternatives. As a result, Egypt will start accumulating USD and the EGP value will rise. Empirical studies disagree. They show that this argument is fallacious on several grounds (at least for Egypt).

First, is what is known in economics literature as the J curve. Imagine that Sami & Co. exports razor blades to Beardistan (don’t waste time googling it). A package costs them 10 EGP and sells at 12. Before the EGP devaluation, a razor blade package cost Beardistan 2.07 USD. Now, with the depreciation of EGP, blades will cost them only 1.82 USD and Beardistanis with lower incomes will afford (the) deluxe Sami & Co. blades. Thus, demand for the blades will increase, driving Sami & Co.’s sales up. The effect reaches every exporting company and the economy will thrive. The J curve holds that it will take Sami & Co. some time to adapt to the increased demand and increase its productive capacity. A study by AUC’s Dr. Hala El Ramly in 2004 found that it would take four years for Egypt’s exports to gain from devaluation. Fiscal deficit and current exchange rate were independent variables in her model, factors that are currently deteriorating; meaning that it will now take us more than the estimated four years. On the import side, we are the world’s biggest wheat importer. Yes, we’ll still import wheat (and other essential commodities) under any cost.

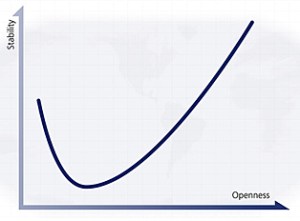

A graphical illustration of J-curve. This is how Egypt’s production will behave after devaluation. The curve will lie mostly below the x-axis.

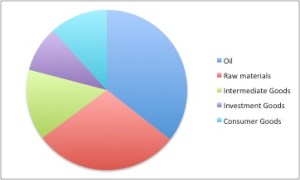

Second, it’s not that simple. Devaluation does not necessarily mean that Egyptian exports will be cheaper! 52% percent of Egypt’s imports are raw materials, intermediate goods and investment goods. Egypt’s exporters’ cost of production will increase as (roughly) half of their inputs will inflate, raising their prices and diminishing the gains from devaluation.

Third, even if there is a gain to exporters, they don’t constitute much of Egypt’s production anyway. Egyptian workers and local firms will bear the costs of rising oil, bread, maize, tobacco, steel, cotton, fruits, vegetables, paper, aluminum, car spare parts, rubbers, telephone calls, refrigerators, dairy products, eggs, honey, sugar, pharmaceuticals and insecticide prices.

There’s no magical button to get matters back to order, though one would question that they ever really were. The government has two main long- term challenges: a sixty-year old socialist burden and angry protestors calling for. . . more socialism (as if 6 million bureaucrats are not enough). In the short-term, it has no other option than securing an IMF loan that will lift subsidies, raise taxes, liberate markets, add up $4.8 billion to our reserves, restore (some) investor confidence, reduce borrowing costs, limit devaluation and open up the door for $14.5 billion of aid and loans conditional on the IMF deal.